Saturday, July 23, 2005

ROCKVALE SCHOOL HOUSE

The Rockvale school was built sometime between 1900 and 1905 (former students and area history books don't pinpoint an exact date). The school was closed in 1948, when the population of western La Plata County an area known as the Dryside declined and Hay Gulch students began attending an elementary school at the old Fort Lewis College campus south of Hesperus.

Rockvale teachers arrived at the schoolhouse to fire up the coal heater and warm the schoolhouse before class started at 8 a.m.

The school day, which lasted until about 4 p.m., mainly consisted of the basic academics: reading, writing, math and social studies with short recesses in the morning and afternoon and an hour for lunch. Windows and kerosene lamps lit the school until electricity came to Hay Gulch in the 1940s.

When I (Luther Butler) went to Rockvale School in the first and second grade there was a bee hive in the north wall of the building.We children spent many an hour catching drones (they had no stinger) so we could attach them to pencils with sewing thread.I wasn't unusual to see a pencil fly through the air as the male bees pulled it around.Once in awhile a student and a bee would have a run in and stings around the eyes would cause the teacher to have a student lead the victim home.

During my first year Scarlet Fever broke out in November, and we didn't have school again until March. One of the eighth graders died of the illness.

Since we lived seven miles from school by the road, we would cut through the woods if the snow wasn't too deep. When it snowed sometimes drifts would get very deep. With the temperature below freezing, we had a good workout twice a day. In spite of the hardships the Rockvale School experience has always been my best school days.

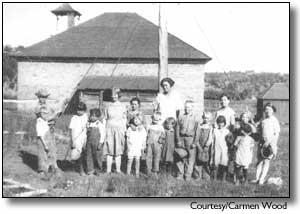

ROCKVALE SCHOOL 1935-36

TOP ROW LEFT TO RIGHT THIRD AND FOURTH GRADE 1.SAM CORDELL 2.LEE SMITH 3.BILLY DUNN 4.CONNIE HUNTINGTON. 5. LINNEL BAIRD/ BOTTOM ROW LEFT TO RIGHT: MAXINE YOUNG (2ND OR 3RD GRADE)/ FIRST GRADE: 1:EARL SMITH 2. JACK HUNTINGTON 3. JOHN BROWN YOUNG 4. ED CORDELL 5. LUTHER BUTLER/ CARMEN CORDELL (4TH OR 5TH GRADE)Miss Binder, teacher for all eight grades, had me sitting with Ed Cordell until we had too much fun, and I had to sit with Maxine Young which I enjoyed a great deal.

Monday, July 04, 2005

LUTHER BUTLER'S EARLY MEMORIES OF LA PLATA COUNTY COLORADO

Durango Herald Online: "Galloping Goose railcar "

LUTHER BUTLER'S EARLY MEMORIES OF LA PLATA COUNTY

CABIN EAST OF MANCOS

On November 14, 1929, my parents were returning to La Plata County after a year in Cleburne, Texas trying to sell a boxcar or two of Delicious apples grown in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. Their journey was halted in Alamosa, Colorado by my birth in a Luthern Hospital. From this hospital, I got my name. I'm thankful they didn't make it to La Plata County for my birth since the hospital in Durango, county seat, was Mercy Hospital. Luther is hard enough to bear, but think of a name like Mercy!

Before my birth, my father had owned a music and a Singer Sewing Machine store in Durango. Many times he had taken land in trade for merchandise so when he returned to La Plata County with me and four other of my siblings, he started developing these rough but very picturesque pieces of property. From all of the land the mountains were either visible or very close.The first place I remember living on was four miles east of Mancos, Colorado. The beautiful piece of forested land was surrounded by mountains that towered over the log cabin we were so proud to own.

D&RGW RAILROAD My most vivid memories of this home was sitting on a front porch that opened up to a view of the D&RGW railroad that allowed a narrow line train to come out of a mountain pass where the train would run west across pasture land and then disappear into more mountains.It is easy to remember the black engine with smoke pouring out while it pulled brightly painted boxcars that rumbled before a red caboose emerged. After all these years, the smell of coal smoke still drifts into my nostrils. Sometimes instead of the train, a bus mounted on wheels designed for the tracks would come bouncing around the bend with a few passengers and the daily mail inside. It was easy to see why this odd vehicle was called the Galloping Goose.

DUST BOWL During the early 1930s, while we were living in a green paradise the people east of us were going through the era of the great Dust Bowl. One warm summer morning a train of canvas covered wagons came down Mancos Hill and proceeded to cross in front of our cabin. The odd thing about this covered wagon train was that the cumbersome vehicles were being pulled, or at this part of the travel down the steep grade, held back by teams of black and white Holstein milk cows that some enterprising dairy men from Kansas were saving from choking dust by making them into draft animals.For several years during the Dust Bowl,it would snow, and when the storm was over there would be a layer of red dust blown in by an east wind. Years later, I would think of this when eating a white cake decorated with chocolate.

FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH, MANCOS During the time we lived close to Mancos, my father filled in on Sunday Morning at First Baptist Church, Mancos. Although he had only finished the fourth grade in Fort Worth, Texas, he was an ordained Baptist lay preacher. Two incidents at First Baptist come to mind. 1. I was approaching four-years-old, and since my older sister took care of me, I was determined to stay with her during Sunday School. One lady with nice silk stockings pulled me out and took me to my class. Determined I would stay where I belonged, she stationed herself across the door. Doubling up, I ran between her legs and returned to where my older sister was. 2. Eventually the church called a business meeting to discuss calling my father to be a full time minister. Most of the people were inclined to vote him in - except one staunch elderly lady. Getting up during the meeting she announced loudly that she had been a member of the church for years, and since she was the Peter of the Church, she didn't want my father as a minister. A group of teen-agers in back of the church auditorium, including my three brothers, grew hysterical at this announcement. Although my father continued to supply, he didn't get the job.

GOAT AND SHEEP RAISING The 1930s were an era of poverty for many in rural La Plata County. Although Mancos was a few miles in Montezuma County from my father’s homestead land in La Plata County, he determined to start using the two places by having his two older sons raise goats. With most of the small homesteaders starved out, he knew he could run his herd across vacant places by paying a small yearly fee. My two older brothers who had dropped out of high school were looking for a means to support themselves and the rest of the family. Sheep were their choice, but with goats more easily traded for, they became the dominant part of the herd.The distance from the log cabin east of Mancos to the homestead near the La Plata River was fifty or so miles, which would have been a long drive. The two young men knew of an old Spanish Trail that went southeast from Mancos to the homestead. The distance was some twenty miles or maybe even less. Therefore, they drove the small herd between the two places. Starting off with primarily goats, which were gradually replaced by sheep, which were easier to herd. The goats would climb the steepest trail to a prominent rock or mountaintop. Bringing them back down became so hard that one or the other brother would use a rifle to bring the wander home.One day when the herd was close to Mancos, some cowboys rode up. “Mr. Butler,” they said, “we want to rent your goats for a rodeo.” The deal called for the goats to be let loose on Main Street in Mancos. Using their pickups as barriers, the ropers were going to offer prizes for the rider who could rope the most goats. A large crowd gathered. The ropers mounted horses and began to unlimber their lariats. The crowd cheered. Firecrackers went off. Dogs yipped and ran after the goats. It was the most hilarious thing I ever saw. Goats jumped into pickup beds, crawled under pickups, and bunched up on the sidewalks. Cowboys went crazy trying for prize money, but I’m not sure that more than three or four goats were caught that day.Soon after this, my father began buying angora goats for the high quality hair that could be woven into beautiful rugs. This time my father planned to put my mother and older sister to work in weaving the rugs. He bought a spinning wheel along with a loom. The last I remember of the rug making equipment was that it sat idle in the cabin. One unfinished rug was on the loom. My mother would cook, cut wood, hoe crops, tend babies, but she would not make rugs!

SHEEPHERDERS My father had traded a piano to a widow for a quarter section of land between Hay Gulch and Alkali Canyon. The land had been opened to homesteaders when the Ute Indians were forced to move to the Colorado River in Utah. The woman’s husband had died before he could build a primitive house (homesteader’s shack) and clear fifteen acres of land both of which were required before the Government would turn over ownership. There were other obstacles two of which were there was no water and the dirt roads became impassable after rain or snow.My mother lived in a tent before my father built a temporary house from upright cedar poles. Apparently, the family preferred living in the log cabin near Mancos until my father could find a way to bring both places into production. While my father tried to make a living by peddling vegetables and fixing sewing machines, my mother and two of the older boys were able to clear the required fifteen acres.As I wrote, many of the original homesteaders had droughted out before I was born in 1929. Vast acres of pinyon and juniper (white cedar) forests surrounded by sagebrush flats lay vacant. On land without enough rainfall to support agriculture, my father and brothers made a living by raising sheep and goats. The latter animals could use the brush better, but they were difficult to herd – and they made the herding of sheep very difficult. By the time I was three going on four, the goats were almost a thing of the past.Over this vast area of land, my brothers herded their flock. Eventually they were able to gain permission from the U.S. Forest Service to lease a large block of land for summer pastures.

When does a child start remembering events very clearly? I could not have been more than four when I was allowed to spend periods of time in sheep camps. After day work was done, my brothers would set up camp. During rainy periods and in the winter, they pitched canvas tents. During clear weather, they would make a camp under the stars. Building a roaring fire, they cooked after which they read. The youngest of the three brothers played a mouth harp and a guitar.Now here we were miles out in the woods away from any dwelling when young men and boys the same age as my brothers started drifting into visit and listen to the music.Story telling was one of the major ways these visitors and my brothers entertained each other. Fighting sleep, I would try to keep my eyes and ears open long enough to hear tales of fighting wild animals, snakes, and chasing rustlers and once in awhile, a killer. My greatest joy was imagining that I was Robin Hood camped with his merry men. Cedar smoke mixed with tobacco were often the last memories I had of a weary day.

HOMESTEAD RUINS By the time I can remember much about the Dryside between Hay Gulch and Cherry Creek, most of the homesteaders had cleared out. Drought, cold weather, low prices, and perhaps muddy roads and who knows what else had caused a general migration to greener pastures. Where there should have been four families on every section, there were abandoned houses that were quickly rotting back into the fertile red soil. Just about every abandoned farmstead still had a few apple trees, a remnant of a flowerbed, and a dirt cellar that was starting to crumble. My youngest sister and I spent countless hours sifting through dirt to find broken plates, corroded eating utensils, and a few books in the old cellars. The house that was a twin to ours still stood a quarter of a mile to the north of our home. A disabled World War I veteran still tried to make a living on his farm located several miles to the North. Seven or so miles to the north, a family of Cordells still raised fairly good crops. To the northwest, a Texas migrant still raised goats and cattle. To the east of us on Hay Gulch where there was irrigation water, several families were making a go of it.My remembrance of this vast beautiful land framed by mountains was abandoned fields pock marked with prairie dog mounds. The Black Book my mother taught me to read out of spoke of desolation of desolations. Except for a land whose beauty could be only temporally marred by humans, the abandoned homesteads were straight out of the writings of the prophet Ezekial!

A couple of miles more or less from our house, along Alkali Canyon, a house still stood along the canyon wall. Some of the rooms had been dug into the sides of the hill, and the walls were lined with rocks. We raised potatoes in the rich loam of abandoned fields where children had once played. Sometimes in my imagination voices of a happy family drifted through the vacant air.

My favorite place to go on Alkali was to a log cabin where an Indian fighter had built a cabin out of logs. There were no windows and only one door. Gun ports had been cut in the walls so the occupant could fire smoking rifles at marauding Indians. Since Navahos had in the early days drifted into this valley, I don’t know if the shots were fired at them or at the Ute who occupied this land until the Government drove them out. The good thing that this location had was a living spring that furnished water for the occupants and their animals. Since the water was contaminated with alkali, I don’t know if it was safe for human use.In this vast, empty land that I loved, my two older brothers and my father (most of the time he was off peddling) tried to make a living by farming and raising a few cows, and a large herd of sheep that numbered around three thousand. Whether my father always paid to pasture the sagebrush flats is doubtful. There just weren’t many people around to collect rent. Most had moved off to far away places and only lawyers in Durango knew where they were. Since much of the land could be bought by paying back taxes, our family started putting every spare dollar into purchasing it. As late as 1947 I was able to buy four hundred acres across Alkali for a thousand dollars. I let the land go back to the owner after a down payment. I wanted to get an education. The next year, gas wells were drilled on this land.

1932. FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT Since I was born November 14, 1929, I was not very old the November day when Herbert Hoover lost the presidential election to Roosevelt, but as though it were yesterday, I can remember my two oldest brothers and my father riding a horse to Marvel in order to defeat the restorer of legal alcohol. We owned a small herd of horses that we used to farm and pack supplies to the sheep camps. Snow had not brought the pack animals out of high La Plata Mountain pasture.Old Dewey was an old horse that we used around the farm for cultivation and short rides. Since he was the only horse available on Election Day, my two brothers and my father took turns riding him to the polls at Marvel. While the three took turns voting, the other two did chores and watched that coyotes did not get into the sheep herd.Although my two brothers were old enough to vote, my father gave them strict instructions on how to mark their ballot. Since voting was by secret ballots, if either brother voted on their own, they never mentioned it while I was around. Hoover had the misfortune of being president when the Great Depression started. Whether he was responsible for the financial mess is for historians to figure out. The only criteria my father and two brothers used in not voting for Roosevelt was that he promised to end prohibition.

Father was the last to ride the old horse to Marvel. While he waited, I went with him to let the sheep graze on last summer’s corn stalks. We built a fire and I listened to a lecture on the dangers of alcohol that Roosevelt was about to release on the country. I was not brave enough to point out that under prohibition there were enough alcoholic beverages being consumed to keep people drunk whenever they wanted to tie one on. Berries, grain, and fermented fruit and vegetables were keeping our neighbors well supplied.Later in the afternoon, we went to the house for lunch and then my father rode Old Dewey up the east road toward the polling place. Since Brother Johnson had opened the church for those who wanted to listen to one the election results broadcast over the sputtering airwaves, I was asleep when he returned, but I heard him regretfully announce that Hoover had lost.

My father, David Homer Butler, born in Liberty, Amite County, Mississippi, around 1890 to a schoolteacher father and a nurse mother never learned to accept the lowly position in life that the Depression tried to force him into taking. With Roosevelt’s New Deal, dignity and prosperity was to come back to rural people of La Plata County. Projects with initals like WPA, CCC, and some other weird letters, were supposed to lift us above the poverty level that my mother thought we were below. Young men around us were soon joining the CCC work force to improve America. The closest camp to us was at Red Mesa, some ten miles away.

My mother told my father that if he didn’t go to work there soon, she was going to apply for Relief benefits. Here my father was faced with the dilemma of going to work for Roosevelt’s plan to end poverty or to my mother putting the whole family on Roosevelt’s great Relief program.With great sorrow my father put on his best brown suit, bought himself a new shiney carpenter’s sqaure and took off for Red Mesa. I watched my proud father walk down the lane toward what he considered the most humiliating thing he had ever done, go to work for the government. My older brothers rejoiced to see him go because they could now farm and raise sheep without his constant bossing. For three days sorrow hung over our home on the Dryside. Ma moped around as though she had lost the most precious thing in her life, my father. On the fourth day we could stop worrying that Father would fall off one of the new buildings he was working on at the CCC camp. He came walking down the hill on our east road. All of us ran out to greet him. It seems he had walked off when his supervisor wouldn’t allow him to take the day off and help a sick neighbor. I don’t remember my father ever offering to help a sick neighbor work before or afterwards. He was not going to work for any government sponsored agency.

How my mother got to the relief office to apply for assistance, I don’t know. In a few days, a smartly-dressed woman in a new car came to fill out the numerous papers that would make us dependent on the State for food and clothing. The haughty woman who stayed all day examined the three younger children. She measured us for new clothing. She left a book that told how my mother should prepare the food the government would soon provide. In other words, in modern terms, she was a pain in the ass.A few days later again her car came down the road. Ma, with great expectations went out to meet her. My youngest sister and I ran out to receive all the new clothes we were going to get. My oldest sister hid in the kitchen.The great dame pulled out a brown grocery sack that contained a box of dried milk, a new pair of underwear for one of my sisters and nothing else. "I’m sorry, Mrs. Butler, but your husband has too much land and livestock for you to qualify for relief." All the way from the sheep shed, we could hear my father let out a cheer. My mother threw the pitiful package back into the government lady’s hands as she told her, "We don’t accept charity."I scuffed my bare feet in the hot Colorado dirt as visions of new shoes and clothing drove east on the road back to Durango. Dad took over his bossing job again.At that moment I was the proudest I’ve ever been in my life before or after. We were poor, but we were not on Roosevelt’s damn Relief.

LA PLATA COUNTY PEOPLE Without neighbors for miles to the south and that much further to the west, part of the time we had no northern neighbors for nine miles, except for neighbors three miles to the east on Hay Gulch, we lived in isolation. Even with few neighbors, people constantly found their way to our door. Cowboys looking for lost cows, prospectors still hoping to make a strike in the mountains, and some just plain drifters came down the dirt road that led to our front door.Robert Frost’s poem, TWO TRAMPS IN MUD TIME, reminds me of what our situation was. In the early 1930s, men were wandering through the country looking to work for food and a place to stay. And, the men who came to our place often came in mud time. Since gravel roads were miles away, our visitors had to either come over frozen ground or slosh through mud and water that soon filled the tracks of the wanderers.One time two men came who claimed they could witch for water – and gold! The talker of the two blew tobacco into the clean air of our house (none of our family smoked) while he told of the magical thinks he could do. Since the locks on the two doors of our house had long since rusted shut, we had taken blocks of wood, drilled holes in the center and turned these stops to keep the doors from opening to unwanted visitors. Barely four-years-old, my eyes grew big as this man told of how he could with his mind, make the door guards twirl. He never did it. A few days later, he moved his starving family into an abandoned house situated three miles from us on the La Plata River. He and his partner tried to support the woman and her children by divining for gold. My parents kept coming up with food. Several years later, the man who was supposed to be a husband and father robbed First National Bank in Farmington, New Mexico with a water gun. We just supposed the desperate man had his divining rod point to the wrong gold.

My two favorite characters were with the Salvation Army in Durango. Dad gave them permission to rob some bee trees for the honey they wished to dole out to starving people in the County. These two were the most jovial people I have ever met. Since my father was a religious zealot, he spent too much time helping others instead of his own family. The bee robbers were robust to the point of being over weight. Although one of my brothers helped them, the two men did most of the work themselves. Early settlers had brought in tame bees that filled hollow cedar trees with gallons of liquid gold still in the honeycomb. Since bee trees were often tall and big around, the two helped by my brother would start a fire, put on green limbs and smoke the bees into submission. Watching these two heavy men run when an angry bee got after them was better than a circus that I had never seen.I have to pause to tell what I had heard about the bees that early settlers brought westward as they traveled. The white travelers often brought small pox with them. Indians who had no immune system to fight the disease often died to the last person in the village. Since bees traveled about thirty miles ahead of their owners, the Red Men thought bees carried the dread disease that poxed their face if it didn’t kill them.When the bee robbers brought in raw honey, my mother would put a wash tub on the wood burning stove and render the honey so it would pour into glass jars. Since my dad would not let anyone rob bees during the cold winter months, the Salvation Army workers came in early spring so the bees would have flowers available. The funniest thing about the two men was that both were stung on their bare bottoms while going to the great outdoors bathroom. The house filled with laughter as these two tried to find soft places to place their sore butts.

<strong>Veterans

I remember two veterans who used to come to our house. My favorite was a Civil War Veteran who would show up unannounced. He and his wife would fill the room with cheer while they took on over we smaller childern. 1933 was a long time after theWar between the North and South had ended. This man must have been at least ninety years old. Always smartly dressed, he would sit in a rocking chair so I could cuddle under his flowing graybeard. What a Northern veteran was doing in the house of a Mississippi rebel I’ll never know, but I’m thankful for the memory he has left me.The other veteran I remembered lived five or six miles to the north of our place, A World War I veteran he had been gassed in the trenches of France. Often out of his mind, he came to our house a few times to hire one of my brothers to work for him. A good farmer, he had been able to hold onto his homestead farm until he was declared insane and sent to Fort Lyons to live out his years behind wire fences. Stories of the crazy things he did drifted into my tender ears. First tried to poison neighbors including our family with some borrowed sugar. Next, he shot a neighbor’s mule when he hired the neighbor to bring his team over and do some plowing. When my father had to testify at the hearing in Durango, we went to town and shopped until the trial was over. For as long as my father lived he grieved over helping send his neighbor to the Veterans Hospital for the Insane.

Members of the Methodist Church at Marvel, Colorado stand out after all these years. Brother Johnson, the minister, often went on peddling trip with my father. His salary was so low that he had to supplement it with other work. The two men would go to Farmington, New Mexico and buy a load of fruit and vegetables. Staying out several days, they would go from house to house peddling their goods. Dad always got the live animals while the preacher got the cash. This is a delicate subject but one day my father brought home a very nice sow. With plans of raising a pigs, he and my brothers borrowed a boar from a neighbor to do the honor. When the boar was turned lose with the willing sow, it was soon apparent that she didn’t have the proper opening to be a mother. We ate hog meat all fall. Since I was barely four I have to this day never understood the deformity.

Lawrence Miller was another of the church members who meant a great deal to me. Stricken with polio when he was a child, he always had to swing his crippled body along between two crutches. When I was diagnosed with polio while in the Navy, Lawrence’s remembrance was my inspiration. Whether it was God's grace or the LSD I was given, I never had to use crutches.

Doctor Smith worked out of his home-office in Marvel. If there are no other people in Heaven, I’m sure he will be there although I don’t remember him being in church. When an epidemic of Scarlet Fever threatened the life of every child on the Dryside and Hay Gulch, three or more times a week, Dr. Smith showed up to try and save my life, and the lives of other sick children. When it was too muddy or the snow was too deep for his automobile, he came in a buggy pulled by a sturdy horse. The epidemic struck in the late fall when I was in first grade at Rockvale School. On the first visit, the doctor nailed a red sign on our door. We were quarantined. No one was allowed to enter the house. My father could buy groceries at Marvel by standing outside and calling his order through the open door. School was closed up before Thanksgiving and never opened again until March.

Doctors at that time were very limited as to what they could do for patients with viral infections. Only in recent times have medicines been developed to kill the germs causing the sickness. In Doctor Smith’s time, only the symptoms could be controlled. When the four children in our house got the disease, my mother cleared the congestion out with her fingers. Kerosene mixed with sugar was of some help. In spite of this, Dr. Smith continued to watch over his patients with careful eyes. A few nights when we were very sick, he stayed at our house to help my mother keep air passages cleared. I remember him trying to doctor us by the light of a flickering kerosene lamp. It would be years before electricity would come to our house.Before the Scarlet Fever, my mother got blood poisoning after a scrape with a rusty wire. Several times the doctor brought in a bone saw to remove her arm above the elbow. Each time he tried one more thing before he cut. In desperation, he poured a bottle of iodine into the wound. It left an ugly scar, but my mother kept her arm.

Dr. Smith never sent a bill. Most of the times he was paid with chickens, hams, mutton, or eggs. How he got money to feed his family or to buy the necessities of life, I don’t know, but he usually drove a nice car. Once in awhile he made a trip to a far off place like California.

Every spring he sold my mother enough calomel to give each member of the family a dose. A white tasteless compound Hg 2 Cl 2 used esp. as a fungicide and insecticide and occasionally an eternal medicine, the patient was not allowed any sugar until they took a laxative to purge the system. Calomel plus sugar I was told, your teeth would loosen and fall out. Although I survived the dosage, sometimes I would have rather died. This copied poem explains the situation well:

Calomel

Ye doctors all of every rank

With their long bills that break the bank,

Of wisdom's learning, art, and skill

Seems all composed of calomel.

Since calomel has been their toast,

How many patients have they lost,

How many hundreds have they killed,

Or poisoned with their calomel.

lf any fatal wretch be sick

Go call the doctor, haste, be quick,

The doctor comes with drop and pill

But don't forget his calomel.

He enters, by the bed he stands,

He takes the patient hy the hand,

Looks wise, sits down his pulse to feel

And then takes out his calomel.

Next, turning to the patient's wite,

He calls for paper end a knife.

" l think your husband would do well

To take a dosc ol calomel."

The man grows worse, grows bad indeed

" Go call the doctor, ride with speed."

The doctor comes, the wife to tell

To double the dose of calomel.

The man begins in death to groan,

The fatal job for him is done,

The soul must go to heaven or hell,

A sacrifice to calomel.

The doctors of the present day

Mind not what an old woman say,

Nor do they mind me when l tell

I am no friend to calomel.

Well, if I must resign my breath,

Pray let me die a natural death

And if I must bid all farewell,

Don't hurry me with calomel.

from American Ballads and Songs, Pound

No tune given: songs well to O Tannenbaum (COPIED)

MICKEY LESTER You will notice that so far I have used very few full names. In Mr. Lester’s case, I’m breaking the rule. When we went the seven miles to Marvel to buy supplies or to attend the Marvel Methodist Church, before we got on the graveled road, we passed the Lester place. A three-room house surrounded by smaller buildings and a large barn sheltering a shed roofed with sod, the house weathered under the Colorado sun. When a small child, we went there often.Before the great stock break of 1929, Mickey had used his wife’s money to run a bank at Marvel. When times were stable, Mickey lent a great deal of money and took land to secure the note. When the depression hit, the couple was left with large tracts of land and very little money.Mickey had one big tragedy in his life that he mentioned frequently. Falling off a hay stack and living, he referred to it "as when he knocked himself sensible."

With every word I write about this man, my heart fills with love for a man who treated a little boy with great kindness. Mickey had been superintendent of the Sunday School at the Methodist Church. Suddenly, he dropped out and joined the Kline Mormon Church that was across a field east of his house.One day my father got up the courage to ask Mickey why he changed churches. Mickey said he had two reasons: 1. The church had a Sunday School picnic at Cherry Creek. Somehow, even though he was Sunday School superintendent, he was not notified. 2. His second reason was the best. From the Mormon Church, he could watch his hen house even when he was supposed to close his eyes in prayer. With a chuckle, he said that the Mormons had left his poultry where they belonged. His scripture for this change started out, "Watch and pray."The last I heard of Mr. Lester, when the Depression ended, he regained his money and a lot more. He had sold his house at Kline to my oldest brother and opened a real estate office in Durango. Apart from selling the same place two or more times, he was doing well.

HORSE FARMING IN LA PLATA COUNTY.Horses were still the main source for La Plata County farming in the early 1930s. A few farmers were beginning to buy tractors, but the initial cost was still out of the range of most depression strapped farmer. The farmers of German descent near Rockvale School used large breeds such as the Percheron to pull their farming equipment. Horses first bred to carry knights in ancient Normandy clomped through Colorado mud.

Large breeds did not fit our needs. My father and brothers had to have draft animals that could also be used to carry packs and riders along narrow mountain trails. Sheep tending required a smaller, sure-footed animal. Our family started their herd with a race horse mare bred to stallions that resembled the modern quarter horse. Strong for farm work, they could climb mountain trails. Some people called these horses, broomtails, but they suited the farmer-sheep raiser better than most animals except the Spanish donkey that was good in the mountains but not worth a plugged nickel for pulling plows and other farm equipment.

I grew up understanding terms such as; single trees, double trees, wagon tongues, Georgia stock, lister, turning plow, mower, hay rake and a multitude of other horse drawn farming equipment.Our horse herd, which consisted of fifteen to twenty animals seldom rested. Spring plowing required two horses to pull the turning plow as soon as the ground was dry enough to turn. After plowing, a team pulled harrows, heavy drags to level the field, then came the one horse planter followed by one or two horse-pulled cultivators. Most of the herd was on its way to the mountains before the crop was big enough to hoe. Except for one or two older horses not suited for mountain packing, the herd would not walk on level ground until snow caused them to come to lower ranges for food. The older horses spent the summer pulling a cultivator.

Since except for water we caught in the cistern, we had to haul our drinking water three miles from the La Plata River a horse or two was needed to pull the wagon used for this task. When no horses were available, my mother would give us smaller children buckets, and off we would go for a picnic and to bring water on our return trip to the house.

When killing frost hit then the horses were hooked to wagon and loads of corn fodder was hauled into fenced areas so deer and other larger wild animals wouldn’t destroy it before it could be fed to the livestock. When snow came, the horses were used to skid cedar post out of the woods. Often times the sale of this fence building equipment was used for our Christmas presents.

Although we always had at least one Model T Ford truck, the roads were not passable except for horses. Snowdrifts and later, mud, would not permit motor driven equipment. I can still remember riding to Marvel holding onto an older member of the family as our mount moved along. The two school-attending children often rode horses the seven miles to classes when the animals were available. When the snow got deep, the horses were hooked to sleds to pull feed to the sheep. My dad bought cottonseed hulls by the truckloads. Fifty gallon barrels of sorghum molasses spread over the dry hulls from southern farms along with corn fodder raised on our fields supplemented the sagebrush and buck brush that the sheep browsed on all winter. This kept the animals alive until weeds growing under the snow emerged to fatten the winter-starved flocks.Horses, besides being beasts of burden, became members of the family. We gave them pet names such as: "Chigger", "Old Bird", "Dewey," "Fanny," and other pet names. We knew the characteristics of each horse, and we knew which ones were fakers when it came to performing their tasks. Old Bird, the mother, grandmother, and great grandmother of our herd, became in her old age, the best faker of all the horses.Since the horses would often go to the Mormon Reservoir, a mile from the house, to drink and graze, they sometimes became stuck in the mud. Old Bird turned up missing one summer day. Soon after a search, she was found bogged down along the Reservoir water. Daddy and an older son cut two large cedar posts from the hillside. Attaching a pulley to a cross bar attached to the posts, a rope was lain out on the mud before it was pulled under the trapped animal. Here the whole family had labored all day under a summer sun to rescue the pitiful mare. Before the rope could be shoved under her muddy body, the old horse stood up, walked out of her trap, and went to grazing!

Marauding bears sometimes spooked the pack animals used in the high mountain pastures. The sheepherders tending the sheep hobbled the horses when they were not riding them or using them for packing. Sometimes when the horses had to escape the bears, they would hop along for miles until the bears gave up or a herder could fire a rifle to either scare or kill the pursuer.

When it came to riding a horse, I have always preferred to go bareback. The other members of my family preferred a saddle. We tried English posting saddles, side saddles for the women, and some other types, but the only one that really worked was the Western work saddle with the roping horn that I feared would ruin my manhood before I had a chance to try it out. I am not ashamed to tell that I have awakened wet with sweat when dreaming about a saddle horn.

For work, we used bridles with blinders over the the sides of the horses’ eyes. For riding, we used bridles with bits that could easily stop or turn the horse. Spurs were not allowed. Once I saw my father pull a neighbor’s boy off one of our horses that he was spurring.At first the only machinery that I saw used on our farm was a threshing machine driven by a steam engine mounted on wheels. The threshers would start on the Dry Side and farms across the La Plata River and then go to farms close to the mountains such as Fort Lewis, Hesperus, and Thompson Park where the grain matured last. We used horses to pull the wagons loaded with sheaves of straw to the thresher. Once there, several men would feed the bundles into the roaring mouth that scared horses so much that sometimes two men would hold them to keep them from running.Huge haystacks accumulated where the empty straw blew out of the thresher’s blowpipe. Sometimes these mounds moldered for years. On our farm, we only raised enough wheat for harvest every three or four year. Drought, deer, rabbits, and violent storms knocked us out of harvesting grain more often. When there was a haystack, the sheep soon demolished it when the snow started falling.

My two older brothers, over my father’s objection, bought a used International tractor. This iron monster was mounted on metal wheels on which the rear ones had steel cleats that dug into the soft soil. When the tractors were moved on pavement or graveled roads, the cleats had to be removed to keep from tearing up the roadbed.

Tractors did farm work much quicker than horses. They did not have to be fed during the winter months. Human labor was cut from crews to one driver, but the machines were not as beloved as the horses that worked so hard.

HOUSING IN LA PLATA COUNTY A few were built of bricks, a few were built of logs, but our three-room house was built of pine boards. A few of the houses had only single walls. We were fortunate to have double walls that kept some of the cold wind out where it belonged. Periodically the older members of the family would mix flour with water to make paste to hold newspapers on the walls to keep the winter cold out. In the front room, there was real wallpaper with flower designs accentuated by a border glued over the paper.

Even though there were always two full sized beds taking up a fourth of the floor space, in the evening there was always room for a picture puzzle, a rocking chair by the light for a reader, and space for a ring for a marble game. When bedtime came the games were put away, and when the three older brothers weren’t in sheep camp, they slept in the bed farthest from the window. My parents slept in a big bed by the north window, and when there was a sick child, my mother crowded it in on her side. The only time I hated the sleeping arrangement was when so many children were in the big bed that I had to sleep at the foot with my father’s feet in my face. Just thinking about it makes me sick.

The front room had a door and three windows through which enough light came to make the room well lit during hours when the sun shone through panes of glass that were clean only after spring cleaning. This room also had a flu with a stovepipe to attach a heater that would burn either coal or wood. My younger sister and I spent many a winter afternoon sitting on the backside of the bed and watching snow fall on the mountains. When it was time for my brother and older sister to come home from their seven-mile journey to Rockvale School, we watched the north field intently for their return.

The kitchen ran along the west side. Built with a roof that sloped toward the west, there was less room to stand by where the back door opened. The north end was partitioned off to make a pantry where shelves contained flour, sugar, salt, and whatever articles my parents could afford. At the opposite end of the room, there was a flu for a stovepipe. With only two windows, on winter days the room was always dark enough to require a lit coal oil lamp. A long table at the north wall has a space for two chairs where my father and mother sat to eat. Down both sides, there were two long benches. Whoever built them left overhang on both ends. When the benches were loaded and one child was sitting on the overhang, those sitting in the safe zone would stand and dump the remaining child on the floor. When the bench came flying up, my parents would swat the guilty parties.

When the whole family gathered around the table, there was friendly conversation spiced with good jokes. After we finished, my father would read to us. Often it was the Bible, but sometime it was a magazine or newspaper article.Sometimes there would be disaster at the meal. Too much food on the spoon, and a small child would choke. One time during the coldest part of the winter my father traded for a stalk of bananas that we hogged down. Suddenly my third oldest brother grabbed his throat and choked out that he had swallowed a biting spider that had been on the fruit earlier. He knew he was going to die so my father prepared to rush him to Doctor Smith. My mother calmly examined the place where my brother was eating. Sticking her finger on a red powder, she tasted of it. The mystery was solved when it was discovered that the hurt one had sprinkled red pepper on his food.

When I starting walking the seven miles to school, one dark wintry evening I sat by the stove with my frozen shoes in the oven to thaw so I could take them off my cold feet. My mother got me a spoon and a soup bowl and told me to dish some hot vegetable soup out of one of two pans on the hot stove. Finally after I couldn’t cut the meat, I stood up and got a knife. My mother told me that there was not any meat with the vegetables. Bringing the lamp off the table, she discovered I had filled my bowl with hot dishwater. The tough meat was the dishrag! We both laughed.

A small bedroom and a closet ended the south end of the front room. Barely big enough for a double bed, my oldest sister had to share her sleeping area with my youngest sister and I. Snuggling closely together, we slept warmly under heavy quilts. Sometimes on snowy afternoons, the three of us would listen to my sister read before we took naps. Summer or winter, if I was sick Sis’s bed was my place of refuge. In the summertime on rainy days, I would watch the tall pinyon trees sway with the strong wind.

During the hot summertime the children moved out and left the house to my parents. The male children slept in a garage that was separate from the house. The two females slept in another out building. Sometime when the weather was good, we would put down tarps and put our bedding on this ground cover. Many a night I remember going to sleep under a star lit sky while coyotes filled the air with their beautiful music. Since then I have slept in college dormitories, Navy barracks, and after I married, in my own house. Never has anything equaled the beauty of sleeping under a Colorado sky!

One thing I’ve almost forgotten about our house was the bed bugs. This copied article describes the critter better than I can. "In most parts of the United States the only bed bug of importance to man is Cimex lectularius. Bed bugs of this species feed on blood, mostly from people, but are also known to feed on bats or other animals including rabbits, rats, guinea pigs and domestic fowl, especially when the animals are housed in laboratories. The bed bug has a sharp beak that it uses to pierce the skin of the host. It then begins feeding, injecting a fluid which helps in obtaining food. This fluid causes the skin to become swollen and itchy. Bed bugs are nocturnal, that is, they feed at night, often biting people who are asleep. Where infestations are severe one may detect an offensive odor that comes from an oily liquid the bugs emit. Bed bugs can be enticed to bite during the day if light is subdued and they are hungry.

DescriptionA mature bed bug is an oval-bodied insect, brown to red-brown in color, wingless and flattened top to bottom. Unfed bugs are 1/4 to 3/8 inch long and the upper surface of the body has a crinkled appearance. A bug that has recently fed is engorged with blood, dull red in color, and the body is elongated and swollen. Eggs are white and are about 1/32 inch long. Newly hatched bugs are nearly colorless." (Copied)The only thing this article doesn’t describe is the misery of sleeping with this horrible nocturnal beast. In the summertime we’d take the beds apart, take them outside, and wash the hardware in coal oil. Then we would put coal oil in container and set the bedsteads in the liquid. This didn’t work. The bugs would drop from the ceiling and feast on our tender bodies. Raw, red splotches would mar our skin for days. The itching would never stop. For some reason since I am grown, I have never seen a bedbug. I certainly haven’t missed them.

Since my parents had relatives who fought in the Civil War, they taught us a song that went: "Said the bed bug to the flea, you bite him on the ankle and I’ll bite him on the knee while we went marching through Georgia." Damn, I feel like cussing when I think of the misery.

MODEL T’s, MODEL A’s AND OTHER FORD JUNK

Although my mother told me she drove a Ford touring car when she was carrying me from Cleburne to Alamosa, she never drove any kind of a motor vehicle after that. The old touring car rusted away under a large pinyon tree that shed countless years of needles on the weathering seat. The family vehicle was a Model T truck and then a Model A that was much more modern. The Model T had three pedals that acted as a shift. Between pedaling for gears and another pedal for braking, the driver was very busy. Luckily using a lever on the steering column controlled the gas and spark.

Ma and Dad would get in the cab, take a sick or smaller child in their lap, the rest of us would climb on the truck bed, and away we would go. Two or three times a year we went to Durango. Perhaps once or twice a summer, I would get a ride to Marvel, but most of the time we would head down the La Plata River to Farmington. Dad would stack vegetables on the truck bed from small farms in New Mexico and then head north to mining towns and isolated homesteads in Colorado. While he fixed sewing machines, he peddled. Farmington had a much longer growing period than did the people closer to the La Plata Mountains where sometimes there would only be sixty frost free days.

During the years I rode in a Model T or A, I never got to ride up or down a steep hill. Both vehicles were built without fuel pumps. The fuel flowed from a tank under the seat to the motor by gravity. This worked well when we were traveling on the level or going down hill. When the truck began to climb, the fuel stopped flowing. The driver would unload passengers, turn the truck around, and back up the hill. From the smallest to largest passenger, we pushed to the top. When we got to the top of the hill, my mother thought it was too dangerous for us to ride. Repeating our journey up the hill on foot, we hoofed it down the other side. Although the brakes were never the best, my dad seldom had any trouble. A few times he ran the truck up the bank and used a tree for brakes.

To add to all the other troubles, there was usually mechanically trouble. To start the motor, an adult had to take a crank, place it in a hole under the radiator and crank until he or she was blue in the face. First, before the cranking, the gas and spark lever had to be in the proper position. Set the spark too low and nothing would ignite the gasoline. Set the spark too high, the motor would backfire and knock the cranker to the ground after a wild ride in the air.The old trucks did not have a battery. The current for running the motor and lights was produced by a series of magnets mounted on a wheel called a magneto. The best use for the magnets when they were no longer functional was to pick up nails and other pieces of metal.

The second oldest brother was the mechanic. By trial and error, he was able to keep the trucks running some of the time. When snow covered the ground, he brought the motor into the kitchen after putting a tarp on the board floor. Carefully, he replaced oil rings, ground piston heads, and fiddled with all the other parts. Aside from the kitchen smelling of gasoline and kerosene, the rebuilt motor usually worked when he bolted it back into the truck. So good did he become at this that when he had to go into the Navy when WWII started, he worked on the planes on an aircraft carrier.

The most memorable event that happened was when the Model T stopped on a drizzly day when we were going to our place near Mancos. For some reason, Ma thought she had to have a certain needle out of her white cotton-sewing bag. Setting on the metal running board, she used both hands to dip into the hundreds of metal pins, needles, etc., mostly etc. My mechanic brother laid the magneto on the truck frame so he could work on it. Without securing it, he gave the crank a hard turn. Sparks jumped from the magnets into the metal truck frame. My mother with her hands still in the bag full of metal screamed. Her long black hair came unpinned and stood straight up. The bag went high in the drizzle coming from the sky. Without looking either way, she ran for my brother while she yelled that, "I’m going to kill you when I catch you!" They went around the truck a dozen times until both of them bent over with laughter while they held onto each other for support. Those magnetos were good for some good laugh. The funniest thing was to hook the wires to the seat of an outdoor toilet and wait for someone to set down. With a turn, electricity shot into the unsuspecting victim. Sometimes the person would scream and run outside without fully dressing!

Windshield wipers, when there was one, were ran by a mechanical device inside that had to be manually ran by the driver, or if the driver, was lucky, by the passenger. I spent a few trips frantically working the device while my father drove through heavy snow or rain. When the temperature was cold enough outside we would have to stop and scrape ice before continuing.

Money was so short that sometime my father would not have enough to buy license plates. Draping a sheepskin with the wool on it over where the plate should be, we would make our trip.

Driving over narrow unpaved roads, and sometimes, un-gravelled roads, was a hazard in dry weather. When the roads were icy or muddy, accidents happened. Once when we going down Wild Cat Canyon to get to Durango, we stopped because a touring car had gone off the road into the water. Sadly we watched two men carry a beautifully dressed lady out of the canyon. I will always remember her hat covered with roses and blood. The worst wreck I remembered hearing about was one snowy night came in from Hesperus to tell us about a man crashing as he came down the road from Mancos. When the car hit a tree, the driver was impaled on the steering column. There was nothing anyone could do as the injured man pleaded for someone to shoot him.

Whenever Dad went for vegetables or cottonseed hulls, when he was due home, we children would gather at the front window to watch for headlights. Since we could see car lights on the Mesa, some three miles away, we waited to see if they were announcing the arrival of our Model A truck.

REMEMBERANCE OF A COUSIN WHO CAME TO VISIT Before I was born, both my father and mother's relatives came to live with my parents in La Plata County. This message is from the son of my cousin."My mother spoke on many occasions of their time spent in Colorado with the Butlers. I wish I had listened more intently. She spoke of hardships of life in Colorado that she had heard about. Apparently there were troubles with Mormons in the early days. Illnesses were a serious matter when medical help was not at hand. Large snowstorms would bring isolation, also jobs held by Butler men, which would keep them on the road a good bit, was the cause of isolation. I do recall that raising of sheep was one of the economic activities.Regarding parallel histories, (Of Jenkins, my mother's family and Butlers, my father's family) I have been impressed by the sameness of the paths followed by our forebears. Of my forebears, (Jenkins) first point of entry into America was, in every case, the Chesapeake country: Virginia, Pennsylvania, or Maryland, between 1650 and 1750. Later, as new lands safe for settlement became available, my forebears showed up in the Carolinas, Georgia, or Alabama, or all three in that order. Mississippi and Louisiana were already settled when the time to leave Alabama came about; it was necessary to bypass these states and move on to Arkansas and Texas, to find new farmlands. Somewhere I heard that southwestern Colorado was one of the last areas of the continental United States, even into the twentieth century, where a family could homestead public lands.

MORMON TROUBLE Apparently, my father and the Mormons at Mancos were friendly. When my father moved to the Ute land, trouble started. There are two sides to every story, but I know only what happened one summer day when I was four going on five. Going to the north of the house I heard someone chopping wood in a grove of trees about a quarter of a mile from the house. When my father and I got to where the noise was coming from, we found a Mormon man from Kline and his two sons loading wood onto a wagon. I don't think my father would have objected to anyone getting a load of wood, but while the father chopped, the two sons were unstapling barbed wire and rolling it up. When we got there, they had several rolls on the wagon. My father grabbed the bridles of the horses and throwing me in, we took the team and the wagon to the sheep shed. Un-hitching the wagon, my father locked the horses in the shed with the intention of making the Mormons put the fence back up the next day. About dawn the next day, twelve Mormons, including the Bishop, rode up. Surrounding the house, they unholstered rifles and threanted to shoot.My mother put my older sister along with my younger sister under the bed in my sister's room. We had only a single shot .22 in the house. My older brother started out the kitchen door just as my mother shouted to him to get the gun. A Mormon shouted that the first person to come out the door would be dead. If it hadn't been that one of the more sensible men hit the gun, my brother would have been dead when the bullet hit the door .My father was sick in bed that day. The Mormons came into the house and carried him out the door and placed him in the wagon. They intended to take him to Kline for a Mormon trial. My mother loaded my youngest sister and me into the vehicle and jumped in herself. My third oldest brother also insisted on coming. The Mormons tried to stop her from coming with the children, but my mother was pretty hard headed.

When we got to Kline, one of the younger Mormons put a rope around my father's neck, and throwing the rope over a limb, he started pulling. Again a saner man interfered. The next day after a trial before the Mormon justice of peace, they took my father and the rest of us to Durango and put us in jail. Luckily my brother got lose and ran to the lawyer's office from whom my father had leased the land. In a short time, the lawyer took us back home after the sheriff arrested the Mormons for stealing wire. I will always remember the fright that I suffered over the incident. It has taken me years to forgive the men who caused the trouble, but now I remember the kindness that some of the Mormons showed us at various times. Once when my mother had a bad infection in her arm, a Mormon lady who lived on the La Plata River land stayed at our house until my mother was out of danger.